Well, it’s official, what I had suspected might happen in the future, is actually already underway: the strong possibility of a collapse of the very base of the food chain. Reading this article in the Seattle Times made me realize I’m already behind the curve.

Now being a former full-time (now part-time) fishing guide and an avid sport angler before that, you can imagine the optimism someone like me must house in order to still enjoy what I do. But, when I read these articles and hear repeatedly that the “souring” of our oceans is much further progressed than scientists have modeled, I (once jokingly) tell my friends that I’m glad I have another job because I don’t think “full-time fishing guide” has a very secure future.

I’ve lived on the Oregon coast for the last 2 decades and although I’ve recently moved out of the tsunami zone (now it sounds like I’m all doom and gloom, doesn’t it?), I don’t feel at all removed from my coastal spawning grounds. A large portion of my food and revenue still come from the sea, and I hope that will still be the case when I’m once again ready to leave this city bustle.

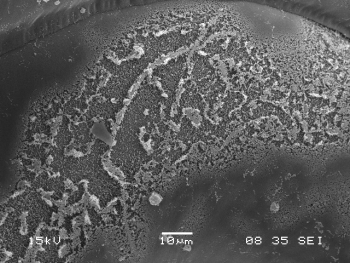

Some good friends of mine own a small oyster hatchery that feeds a large oyster industry on the Pacific coast. Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery is actually the largest shellfish hatchery in the United States, I learned, but they’ve had a monumental problem they’ve had to overcome. Strong ocean upwelling has brought the wrath of an acidic ocean upon their oyster spat, causing massive mortalities in recent years. Fortunately, local area policy-makers have helped bring valuable resources to the hatchery, controlling the pH of the incoming water, increasing survival rates to ensure juvenile oysters once again fulfill the region’s multi-million dollar industry that hungers for product.

Since Whiskey Creek went into operation over 35 years ago, they had never witnessed the silent anomaly that claimed so many of their juveniles in recent years. Prior to the water quality modifications, they were losing upwards of 70% to 80% of their seed. They currently have the problem under control, but it has required hundreds of thousands of dollars in water-quality equipment to solve the problem.

My question is, if this problem is happening in Oregon’s cleanest estuary, and it takes hundreds of thousands of dollars to remedy this problem in such a small, controlled environment, what the heck is going on in the mighty Pacific? If the hard shells of an oyster are being compromised in this environment, what the heck is going on with the sensitive exoskeletons of our much more sensitive pteropods or crab larvae, which make up the bulk of the food source for juvenile salmon? You can’t help but wonder if we’re already on the brink of a major ecological collapse.

What’s most frightening is that scientists believe we’re too far down the path to halt the coming trend. We’re just now seeing the effects of our careless consumption of fossil fuels from decades ago, and while policy-makers are playing politics with global climate policy, our food base is literally dissolving away.

The crux of the article is about building ecosystem resilience in the ocean, a theme that not many people subscribe to. We, as humans, are more likely to be responsive to a crisis, especially one at the global scale, versus pro-active in keeping it from becoming a true crisis. In order to build resilience, one has to be pro-active.

It’s clear by now that the higher-ups aren’t going to do this on their own. As with many conservation initiatives, they need to feel the political pressure from their constituencies before they make it a higher priority on their to-do list. This is assuming they believe the situation can reach the critical stage in the first place. We have to hope that they pay attention to the emerging science that is being presented to us on a regular basis these days.

Three of the most effective ways to build resilience are to end the over-harvesting of the ocean’s resources, to stop pollution before it reaches our waterways and to implement ecosystem-based management strategies that protect highly productive tracts of territory, aquatic or terrestrial. Once again, we look to the Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) reauthorization to get this done in U.S. waters. It was a cutting-edge piece of legislation when it was enacted and needs tweaking every once in a while to catch up with science and our community’s needs. The MSA does look at protecting critical stocks of forage fish but without taking a hard look at how we protect the very forage those forage fish rely on, what good will it do?

In the very near future, our community will have to come forward as one, demanding that our fishery managers and policy-makers take a hard look at protecting these incredible natural resources for our generation and the next. What seems to be coming to fruition is that this crisis may not land in the lap of future generations, it seems to be taking root right now.

Top photo by Tiago Fioreze, courtesy of Wikipedia

Pingback: Building resiliency in the face of ocean acidification | Ocean acidification

Scary stuff Bob. I don’t take a single salmon or steelhead for granted. They may not be around much longer.

Pingback: A Time of Thanks: Happy Salmon Season to All | Marine Fish Conservation Network

Pingback: All Politics is Local (Even the Fishy Politics) | Marine Fish Conservation Network

Pingback: Soapbox Update Oil and Coal Don’t Mix with Water: by Bob Rees | Oregon Fishing Reports by Oregon Fishing Guides

Pingback: Oil & Coal Don’t Mix with Water | Oregon Fishing

Pingback: Oil & Coal Don't Mix With Water: Protecting Our Fresh Water & Fisheries - Marine Fish Conservation Network

Pingback: Soapbox Update: Warm Water Blob Strikes Again? by Bob Rees August 19th, 2016 | Oregon Fishing Reports by Oregon Fishing Guides

Pingback: Headlines Read: Warm Water Blob Consumes Bulk of 2016 Columbia River Salmon Returns - Marine Fish Conservation Network

Pingback: Soapbox Update: Chain Reaction: How Far Will Our Fisheries Fall? by Bob Rees November 24th, 2016 | Oregon Fishing Reports by Oregon Fishing Guides

Pingback: Chain Reaction: How Far Will Our Fisheries Fall? | Oregon Fishing

Pingback: Chain Reaction: How Far Will Our Fisheries Fall? - Marine Fish Conservation Network