As Conservation-Minded Anglers, We Should Support This

Top Photo: Squat Lobster on Coral in Nygren Canyon. Credit: NOAA OKEANOS Explorer Program, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition

Last year the Obama Administration announced that it was considering what could possibly be the nation’s first marine monument off the continental U.S. Of course, it touched off a firestorm.

The truth is that this doesn’t immediately or directly affect anglers in the Mid Atlantic, or even up in New England really. Yet, it is still significant to us for a number of reasons.

Let me start off by making it very clear early on here that there is very little, if any chance that recreational fishing, save for maybe deep dropping (and I’m talking about REALLY deep), would be prohibited in such an area (note, the closest point is 150 miles from land). Yes, there would be some impact on commercial fishing, but despite all the rhetoric, that impact seems to be relatively small in the grand scheme. And quite honestly, such impact would seem to pale in comparison to the benefit of permanent protection of what appears to be some extremely biodiverse and critically important parts of the ocean, from things like offshore energy development, mining and other industrial uses, and, of course, commercial fishing (even though relatively little fishing actually occurs in these areas).

But let’s start from the beginning so I (we) have everything straight here.

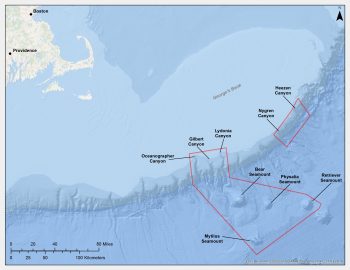

What we’re talking about protecting here are the five northeast canyons and a few very rare seamounts in some really deep water. Specifically, Oceanographer, Gilbert and Lydonia Canyons, which start southeast, about 150 miles off the tip of Cape Cod. The Nygren and Heezen Canyons, which lie approximately forty and sixty miles northeast of those three canyons would be covered also.

Never heard of these canyons? Well, that’s because very few people have the range to fish them, and so, few boats do.

Bear, Physalia, Mytilus and Retriever Seamounts, 25-75 miles southeast of those canyons, would receive protection also. These are old volcanoes that rise as high as 7,700 feet above the ocean floor, the largest of which spans almost 20 miles across.

Colorful Coral in Nygren Canyon. Credit: NOAA OKEANOS Explorer Program, 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition

So yes, we’re talking about a pretty large, far away, yet very unique area. According to recent research, large swaths of the bottom here are covered with coldwater corals – some the size of small trees… centuries, if not thousands of years, old. There are extraordinarily unique habitats here that support a huge diversity and abundance of marine life. To date, the area harbors 1,671 documented species, with estimates of an additional 50% yet to be discovered. That’s insane!

These areas are largely unexploited now; monument designation would keep it that way.

But this is hugely contentious for a number or reasons.

At the forefront is the idea that this is some sort of partisan push-through. Opponents don’t seem to agree that the President has the authority to enact such protections, without Congress, without the Fishery Management Councils. But it’s pretty clear that he does.

In 1906, Congress passed the Antiquities Act, which deliberately gave Presidents the authority to establish national monuments to protect significant natural, cultural or scientific areas. It was put in place precisely because of the situation we are in now, where a few who benefit from exploitation thwart protections of critical areas for their larger value.

Since it was enacted, it has been used more than 100 times by both Democratic and Republican presidents to protect some of the nation’s most unique areas. Let’s be clear that this is not a Republican vs. Democrat issue, nor is it an Obama Administration overreach as some politicians are painting it out to be. I would note that the G.W. Bush Administration created four monuments in the Pacific Ocean covering over 300k square miles.

Next is the idea that there hasn’t been adequate notice, the public hasn’t been allowed weigh in on the potential monument, and that this is being pushed though too quickly without proper vetting.

Not true. There has been and continues to be plenty of opportunity for public input. Last September NOAA held a public meeting and opened a public comment process. In response, a ton of stakeholders weighed in. The comment period has now been open for eight months and, and while yes, there’s been adamant opposition, over 160,000 public comments have come in support of the proposal. Arguably, the Administration has gone out of its way to provide opportunities for public input.

Opponents of the monument proposal contend that any such large-scale protection/management decisions should be made by the New England Fishery Management Council, which debatably allows for a more transparent/public process.

Well, for one, such Councils really only manage fishing impacts. Sure they could ban destructive fishing gear there, but they have no authority to address non-fishing impacts, such as energy exploration, or other industrial activity. Even when it comes to fishing impacts, the Councils’ main priority—in fact, their legal charge—is maximizing yield, not protecting ecosystems.

Regardless, let’s be straight about that Council. It’s no secret that it hasn’t really had a good track record with this sort of thing. Just last year, as part of its Habitat Omnibus Amendment, it voted to reduce the amount of essential fish habitat protected by more than 60 percent.

Yes, the Council has been discussing a coral protection plan for years, but as far as I know, it has been really slow to move on one. Even if I’m wrong on that, it’s very unlikely whatever plan they would develop would give the seamounts and canyons the protections they need to remain healthy and intact.

Why? Because really, that Council currently is, and has historically been, dominated by the fishing industry. It’s hard to argue they represent the broader public who clearly seem to support broad and comprehensive protection.

Again, this sort of special interest thing is precisely why the Antiquities Act exists.

Next is the idea that closing these areas will have a “devastating” impact on New England’s commercial fishing fleet.

I’m not sure I buy that. In the grand scheme, very little commercial fishing activity is associated with these areas. I mean, fishing with mobile bottom gear generally doesn’t occur here because of its depth and ruggedness. And the Oceanographer and Lydonia Canyons are closed to mobile bottom gear under multiple fishery management plans anyway.

While no bottom dragging currently occurs at the seamounts, minimal bottom trawling (according to catch data, less than one percent) for Loligo squid and butterfish occurs around the heads of the five canyons. But is one percent really significant here?

Yes, there are lobster boats that currently fish this area and would likely be impacted by such a monument. But really, how much of an impact are we talking about? Based on a recent survey conducted by fishery managers, only a handful of lobster boats fish here (five to eight boats) and most of them can and already likely do fish in other areas. In fact, the entire area under consideration accounts for only 3 percent of the federal permits and 8 percent of the total lobster catch. And the Canyons and Seamounts area is only a very small fraction of that management unit.

The red crab fishery will also likely be impacted. But this is a very small, limited-access fishery. And the five canyons in the proposed monument area are located in the red crab fishery’s least productive area, according to the New England Council. The red crab fishery utilizes the canyons and continental shelf all the way from North Carolina to the U.S.-Canada border, and the vast majority of red crab landings are from outside the proposed monument area.

Yes, pelagic longlining for swordfish and tuna occurs throughout the area. However, it covers only about 0.3 percent of the total area actively used for the longlining fleet and provided an estimated one percent of its 2006-2012 average annual revenues. Again… Not all that significant.

And really, it’s hard to believe that fishermen couldn’t readily compensate for any closure by shifting to nearby areas.

With that in mind, there’s been a lot of chatter about “effort displacement,” and how closing such an area would just redirect effort to areas that wouldn’t be able to sustain it. Well, I don’t believe that is true either, because when you consider how few people fish here now anyway, how can any such effort displacement be significant?

The point of all this is that yes, there probably would be some impact, but it wouldn’t be huge… Certainly not near what the industry is claiming.

What it all boils down to really is a simple cost-to-benefit analysis. While the impacts on industry overall appear to be minor, the impacts on ecosystems – remember some coldwater corals are hundreds even thousands of years old – would probably be severe should industrial use of the area occur, or should some new fishery develop that would destroy the bottom (both distinct possibilities).

So now let’s touch on all those benefits.

For one, keeping such an area healthy and intact could help sustain and increase productivity in surrounding fishable areas… The so-called “spillover” effect.

Secondly, there’s scientific consensus that protected areas are a hedge against climate change impacts. Recent work by the Gulf of Maine Research Institute has made it abundantly clear that New England’s waters are warming faster than almost any other ocean area in the world. According to scientists at NOAA and elsewhere, large-scale marine habitat protection is one of the most significant things the U.S. can do to build resilience. The Administration has repeatedly emphasized the need to set aside marine refuges “to help sustain biodiversity” as the ocean acidifies and warms.

Yet the main benefit as I see it is this: What we’re talking about here is protecting an exceedingly rare area in an otherwise great expanse of featureless deep water. I mean, undoubtedly, the New England Coral Canyons and Seamounts represent biodiversity hotspots.

As anglers we intuitively understand that what happens here likely affects what occurs elsewhere. For instance, high densities of krill that occur in deep waters of the canyons are transported by currents to Georges Bank. Scientists note this may be an important contribution to the elevated productivity of the areas waters inshore of the proposed monument area.

And this is just one thing we know about! It’s pretty clear that there are all kinds of processes going on in these biologically rich areas that are likely very important to the fishing. We just don’t know about them yet.

The point is these areas are really freak’n important. Not just locally, but likely regionally. As anglers we need healthy ecosystems and an abundance of marine life to be successful. It’s not unreasonable to believe that if this area gets exposed to industrial use, it would negatively affect us.

But forget about that sort of self-interest for a moment. As conservation-minded anglers and ocean users/lovers, protecting biologically rich areas is just intrinsic. We know it’s the right thing to do.

These areas deserve and really need the kind of protection that would come with monument designation.

And make no mistake… They are at risk. Sure, up to now they have been largely protected because of where they are, their depth and the ruggedness of the topography. But such barriers inevitably won’t last.

Ongoing advances in fishing technology, depletion of inshore fish populations, shellfish impacts associated with coastal acidification, possible new markets and other factors will likely make the canyons and seamounts more attractive targets for fisheries over time.

Furthermore, as offshore drilling extends into deeper and deeper waters and deep seabed mining becomes more economically viable, we can fully expect this sort of threat to increase.

The window for protecting the New England canyons and seamounts is closing.

Designating them as part of a national marine monument with clear direction of how the area will be conserved and managed would ensure comprehensive protection… for the long-term.

As an ethical, conservation-minded recreational fishing community, we should support the New England Marine Monument Proposal.

You can do so by emailing the President at president@whitehouse.gov, and/or you can sign the petition.

I am a long-standing conservationist and environmentalist. I happened to be a fisherman in the ocean off California when one of the Union Oil rigs released thousands of barrels of crude oil into the Santa Barbara Channel in 1969. As a result of that spill a bunch of us got together and created GOO, Get Oil Out. It’s not US fishermen, commercial or recreational, that are despairing the ocean, it’s oil rigs, plastic, garbage from cruise ships, US Navy sound test and experiments, a coming wave of offshore wind turbines that are mostly responsible. I’m for sure how monuments as long as they don’t hurt our fishermen and fisherwomen.

Pingback: Of Anglers & The New England Marine Monument - Marine Fish Conservation Network