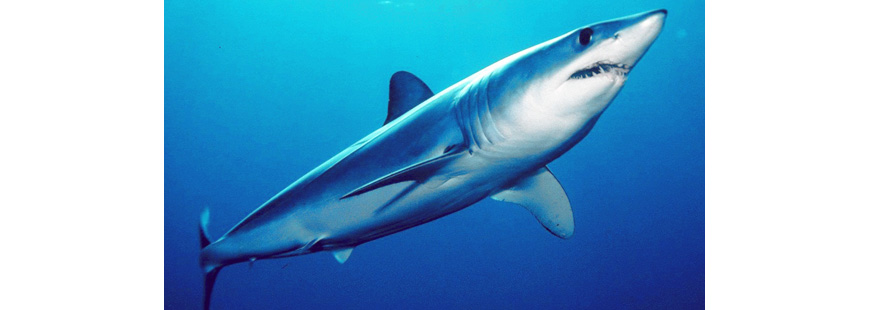

Top photo by by Mark Conlin, SWFSC Large Pelagics Program

In September 2021, at a meeting of the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), the United States, supported by the European Union and other nations, proposed that NAFO ban the retention of Greenland sharks accidentally caught in the Arctic and western Atlantic waters that fall under such organization’s jurisdiction. Intentionally targeting Greenland sharks had been prohibited by NAFO since 2018.

Many species of shark take many years to mature and have very low rates of reproduction, characteristics that can make shark populations vulnerable to even modest levels of fishing mortality. The life history of Greenland sharks is particularly problematic. They can live for at least 272 years (based on a tissue sample taken from an individual of that age), and perhaps for more than 400, and females might not become sexually mature until about 150 years old.

Scientists have characterized the species as “both data deficient and vulnerable to human threats such as fishery-related mortality.” Because of “possible population declines and limiting life-history characteristics,” the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has included Greenland sharks on its Red List as “Near Threatened.”

Given those concerns, it is entirely reasonable for the United States and European Union to take a precautionary approach and call for an end to all Greenland shark landings. While such proposal was withdrawn at NAFO’s 2021 meeting due to objections from Iceland, the supporting parties intend to reintroduce it next year.

When the conversation shifts to conserving shortfin mako sharks, a species frequently landed by both the U.S. and E.U., the picture changes completely. Although a prohibition on landings is strongly supported by the most recent stock assessment, such prohibition has been actively opposed by both the United States and the European Union.

The issue first arose in 2017, when two different studies revealed that shortfin makos were probably experiencing excessive levels of fishing mortality.

One study, conducted by a team of scientists from Nova Southeastern University, the University of Rhode Island, and other institutions, was limited in scope. It saw 40 shortfin makos, caught in the western Atlantic Ocean, released after being fitted with satellite tags, which allowed the researchers to obtain real-time information on the tagged sharks’ location.

To the scientists’ surprise, the satellite tags revealed that 30 percent of the tagged makos were soon caught again; each such shark only had a 72 percent chance of surviving for a year without being recaptured. Their fishing mortality rate was ten times higher than previous estimates, which were based on the reported recaptures of makos implanted with traditional dart tags, and raised concerns that fishermen were killing too many shortfin makos.

Such concerns were echoed in a report issued by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) which, despite its name, has been granted the authority to manage all of the Atlantic’s highly migratory species. Such report found that the North Atlantic stock of shortfin makos was in decline, and that such decline could only be averted if fishing mortality was reduced by 80 percent. Yet even such a large reduction would only provide a 25 percent chance of rebuilding the population by 2040.

In response to the ICCAT report, a group of conservation organizations wrote a letter to the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), asking that the United States take the lead in shortfin mako conservation, and support a complete prohibition on retention. If that were done, the organizations noted, there would be a 54 percent chance of rebuilding the shortfin mako stock by the same 2040 deadline.

The United States ignored such request. Instead, at ICCAT’s 2017 general meeting, the U.S. supported “measures to reduce fishing mortality and efforts to further strengthen data collection, while protecting opportunities for U.S. commercial and recreational fishermen to retain small amounts of shortfin mako sharks.”

Fishermen kept landing shortfin makos, and the species prospects got worse. ICCAT released a new stock assessment in 2019, which stated that

regardless of the [total allowable catch] (including a [total allowable catch] of 0), the stock will continue to decline until 2035 before any biomass increases can occur; a [total allowable catch] of 500 tons has a 52% probability of rebuilding the stock levels above [the spawning stock fecundity needed to produce maximum sustainable yield] and below [the fishing mortality rate that will produce maximum sustainable yield] in 2070; to achieve a probability of at least 60% the realized [total allowable catch] would have to be 300 tons or less…All the rebuilding projections assume that the [total allowable catch] account for all sources of mortality—including dead discards.

Given that some level of discard mortality, particularly in the pelagic longline fishery, is inevitable, the 2019 stock assessment effectively advised against any retention of shortfin makos that were still alive when caught.

Declining mako abundance began to draw real international attention. At the 2019 meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), Mexico offered a proposal to list shortfin makos on CITES Appendix II.

CITES states that “Appendix II includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but in which trade must be controlled in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival.” Thus, an Appendix II listing would not prohibit the harvest of, or international trade in, shortfin makos. It would merely seek to conform such trade to the needs of the stock.

More than fifty nations signed onto Mexico’s proposal; at the time, it was the greatest support given any listing proposal in the forty-six year history of CITES. Yet the United States voted no. Fortunately, it was in the distinct minority; while the U.S. opposed the Appendix II listing, the proposal received the support of over two-thirds of the treaty nations, and so was adopted.

That was the mako’s only international success. At ICCAT’s 2019 meeting, ten nations, led by Canada and Senegal, followed the advice of ICCAT scientists and proposed a ban on all retention of shortfin mako sharks. Six other nations, including some, such as Japan and China, which frequently oppose conservation efforts, supported the proposal as well. But the United States, joined by the European Union and Curacao, prevented such proposal from moving forward.

The United States presented the only proposal that would allow fishermen to retain makos that were brought to the boat alive, a position so unpopular that, of all the ICCAT nations, only Curacao chose to support it.

Sonja Fordham, president of Shark Advocates International, commented that “North Atlantic mako depletion is among the world’s most pressing shark conservation crises. A clear and simple remedy was within reach. Yet the EU and US put short-term fishing interests above all else and ruined a golden opportunity for real progress. It’s truly disheartening and awful.”

ICCAT’s 2020 annual meeting was no less disheartening and awful, as Canada and Senegal again offered a proposal to prohibit all retention of shortfin makos, which again failed because of U.S. and E.U. opposition.

At that meeting, the United States again presented a proposal that would allow the retention of live makos. Such proposal, which would have permitted the retention of live fish only if the nation where a fishing vessel is registered “requires a minimum size of at least 180 cm fork length for males and of at least 210 cm fork length for females,” was clearly intended to protect the U.S. recreational mako fishery, which currently functions under precisely those rules, although it would have permitted the retention of live makos encountered in the commercial fishery as well.

By that time, Canada had already decided that it shouldn’t wait for ICCAT to act, and unilaterally prohibited any retention of shortfin makos by vessels under its jurisdiction.

Now, the United States finds itself in an anomalous position.

On April 15, 2021, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, NMFS’ parent agency, issued a so-called “90-day finding” regarding shortfin makos, declaring that

We, NMFS, announce a 90-day finding on a petition to list the shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and to designate critical habitat concurrent with the listing. We find that the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that the petitioned action may be warranted. Therefore, we are initiating a status review of the species to determine whether listing under the ESA is warranted. To assure this status review is comprehensive, we are soliciting scientific and commercial information regarding this species.

A 90-day finding that an Endanhgered Species Act listing may be warranted is far from a guarantee that such listing will occur. It is very possible that, after a comprehensive status review, NMFS will decide that such a listing is not justified. Still, finding does suggest that, after reviewing all of the information presented in the subject petition, NMFS believes that there is a reasonable chance that the shortfin mako’s plight could be dire enough to warrant a listing. Comments on the finding were due by June 14, 2021, there’s at least a remote chance that NMFS’ review will be completed before ICCAT meets again in November.

Whether or not a final decision is rendered before the next ICCAT meeting, it’s not unreasonable to presume that, if the shortfin mako stock is in enough trouble that an Endangered Species Act listing is even possible, the United States would support a retention ban. But that does not seem to be the case.

In July 2021, ICCAT members engaged in a three-day intercessional meeting dedicated to shortfin mako management. By then, the stalemate over management measures had gone on for so long that the Chair of the meeting asked that nations try to find some basis for agreement before such meeting began, and even took the very unusual step of providing his own proposal for the delegates’ consideration.

Ahead of the meeting, the American Elasmobranch Society, which represents the nation’s shark scientists, sent a letter to NMFS supporting a retention ban.

But those efforts seem to have been futile. The E.U. and U.S. still insisted on retaining makos, while the U.S., seeking to protect its recreational fishery, demanded the ability to harvest live mako sharks. The United States’ position appears to contradict not only NMFS’ 90-day finding, but its stated policy on shark management.

The 500 metric ton annual catch limit proposed by the U.S. would only have a 52 percent probability of rebuilding the shortfin mako stock by 2070. Yet Draft Amendment 14 to the 2006 Consolidated Atlantic Highly Migratory Species Fishery Management Plan states “when addressing management measures for overfished Atlantic shark stocks, NOAA Fisheries’ general objective is to rebuild the stock within the rebuilding period with a 70-percent probability…NMFS uses the 70 percent probability of rebuilding for sharks given their live history traits, such as late age at maturity and low fecundity (i.e., instead of 50 percent, which is commonly used for other species)…”

Given such policy, and the United States’ acknowledgement that the shortfin mako may be in peril, it’s not clear how the U.S. can continue to oppose a full retention ban when ICCAT convenes later this year.

It had no problem sponsoring a similar retention ban for Greenland sharks, even though some recent research suggests that they may still be relatively abundant; it is very possible that Greenland sharks are less imperiled than shortfin makos are.

But Greenland sharks rarely reach U.S. waters, and United States fishermen, whether recreational or commercial, neither target nor harvest the species. That makes Greenland sharks, like elephants and Bengal tigers, easy species for the United States to conserve.

But the North Atlantic’s shortfin makos are different. They swim off every state between Maine and Texas, and both commercial and recreational mako landings make small but significant contributions to local coastal economies. Calling for a ban on shortfin mako retention would have real economic consequences, and make NMFS few new friends in the fishing industry.

Thus, in the case of the shortfin mako, unlike that of the Greenland shark, economic and environmental concerns are in immediate conflict. So far, dollars have ruled the debate. In November, new leadership at both the Commerce Department and NMFS will have an opportunity to prove whether they are willing to make the sort of hard choices needed to conserve and rebuild the North Atlantic’s shortfin mako stock, or whether they will only lead the fight to protect sharks found off other nations’ shores.

Pingback: North Atlantic Mako Sharks Are Endangered — Now What? • The Revelator