Photo by John Papciak, North Bar Media

An operational stock assessment, released in August 2019 (Bluefish Assessment) advised that bluefish are overfished.

In response, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council (Council), in conjunction with the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s (ASMFC) Bluefish Management Board (Bluefish Board), is preparing a Bluefish Allocation and Rebuilding Amendment (Rebuilding Amendment). Pursuant to the provisions of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, that amendment must be implemented by the fall of 2021, and must rebuild the bluefish stock to its biomass target within ten years after implementation.

East Coast anglers had noticed a decline in the number of bluefish over the past few years, but many were still surprised by the Bluefish Assessment’s conclusions, as recreational fishermen account for most of the bluefish landings, and anglers release about two-thirds of the bluefish that they catch.

Yet one of the curious features of the bluefish management plan is that anglers are effectively penalized for releasing fish.

In most fisheries, anglers release all or part of their catch in order to help conserve heavily fished species, and maintain or even increase abundance. But in the current bluefish management plan, if anglers don’t harvest their entire quota, the Council and Bluefish Board may agree to transfer that unharvested quota to the commercial sector.

Thus, in the bluefish fishery, catch-and-release doesn’t accomplish its intended goal; fish released by anglers don’t necessarily lead to increased abundance, but merely to a larger commercial kill.

Many anglers had hoped that the Rebuilding Amendment might change that strange situation. They argued that a fishery dominated by recreational fishermen, who released the greater share of their catch, should be managed for abundance, and not for yield. That argument appears to have fallen on deaf ears. When the Council and Bluefish Board met on May 6, 2020 to consider options that should appear in the Rebuilding Amendment, they did not include an option that would end the transfer of recreational quota to the commercial sector.

The only consideration they gave to the release fishery came in the form of an option that would allocate bluefish based on catch, rather than on landings, but even that concession was illusory. The option defines “catch” as a combination of landings and dead discards, which amount to about 15 percent of all releases, but omits all bluefish that anglers catch which subsequently survive release. Even if the option is adopted, and anglers receive a larger share of the overall quota, the end result will remain the same, for unless anglers kill their entire allocation, unharvested bluefish quota may still be transferred to the commercial sector.

The Council and Bluefish Board never seemed to acknowledge, or even accept, the value of the catch and release fishery, even though such fishery provides real recreational and economic benefits. By reducing the number of fish killed on any given trip, anglers can spend more time on the water, without overfishing the stock. And the more time anglers stay on the water, the more money they’ll spend on fishing.

Saltwater fishery managers just seem oblivious to such benefits. They focus solely on harvest, and maximizing each year’s yield.

In freshwater, things are very different.

The rivers that flow through New York’s Catskill Mountains are some of the most revered trout streams in the world. They receive heavy angling pressure. And in many portions of them, catch and release is the rule, and anglers aren’t allowed to keep any fish at all. In other places, harvest is permitted, but discouraged by both anglers and fishery managers.

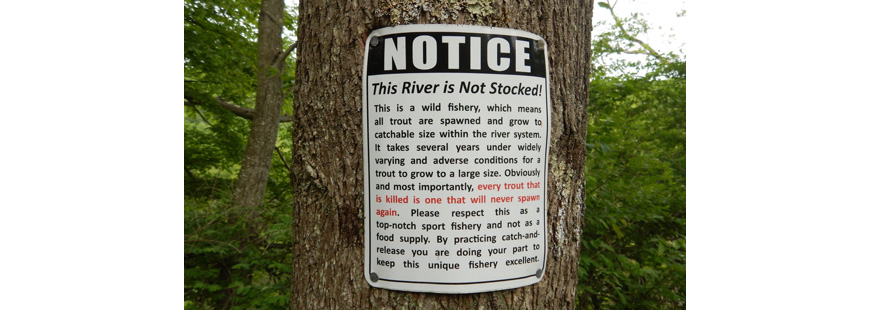

A sign on the Delaware River expresses the prevailing attitude. It reads:

This River is Not Stocked! This is a wild fishery, which means all trout are spawned and grow to catchable size within the river system. It takes several years under widely varying and adverse conditions for a trout to grow to large size. Obviously and most importantly, every trout that is killed is one that will never spawn again. Please respect this as a top-notch sport fishery and not as a food supply. By practicing catch-and-release you are doing your part to keep this unique fishery excellent.

The river’s trout anglers generally respect that sentiment. As a result of the catch-and-release policy, whether it is legally or culturally enforced, the Delaware watershed holds many large trout, and hosts a correspondingly large number of anglers, who fish the river from spring through the fall, and provide substantial benefit to a region that would otherwise be dependent on hardscrabble farms, a waning resort industry and a ski industry that is already feeling the effects of warming winter weather.

Yes, there are anglers who aren’t happy with catch-and-release fisheries, who rue the lack of stocked fish, and who even, at times, poach some large fish from a no-kill section of river. But on the whole, New York’s freshwater fisheries managers appreciate the impact of catch-and-release fishing on trout and other fish populations. The state’s fresh water fishing regulations guide lists over 100 different waters where only catch-and-release fishing is allowed, at least for some species.

New York’s freshwater fishing guide even goes so far as to advise anglers that, “Although a good fish dinner can be the climax of a great fishing trip, more and more anglers have come to realize that quality fish populations can only be maintained if catch and release angling is practiced. This is particularly the case for large gamefish that are typically rare in a population and usually take an extended time to grow to a quality size.”

States don’t make similar efforts to promote catch-and-release in saltwater fisheries. The benefits of catch-and-release apply to those fisheries, too, where overharvest can also frustrate efforts to maintain quality fish populations and eliminate most of the so-called “BOFFFs,” the ” Big, Old, Fat, Fecund, Female” fish that are critical to maintaining a sustainable spawning stock. Yet, except in the case of fish with little or no table value, such as Florida tarpon, saltwater managers rarely if ever manage fisheries for catch-and-release.

Instead, the emphasis is always on maintaining landings at the highest level that can be prudently maintained and, often, a bit beyond that.

Bluefish may be the most blatant example of such harvest-oriented approach, given the quota transfer provision in the management plan, but the pro-harvest philosophy affects many different species. We see it in the striped bass fishery, where recreational fishermen account for 90 percent of all fishing mortality, and about 90 percent of anglers’ catch is released.

Such a fishery would seem to be a prime candidate for catch-and-release oriented management, but that’s not what we see at the ASMFC’s Atlantic Striped Bass Management Board (Bass Board). While some Bass Board members are very conservation-minded, others still cling to the goal of maximizing the kill.

At the October 2016 Bass Board meeting, after a stock assessment update indicated that fishing mortality was very slightly below the fishing mortality target, some Bass Board members immediately attempted to relax striped bass regulations in order to increase landings, even though the female spawning stock biomass remained below the target level.

Even after a more recent benchmark stock assessment found the striped bass stock to be both overfished and subject to overfishing, there was resistance to limiting harvest. In Maryland, managers went so far as to eliminate the spring catch-and-release season, so that anglers fishing from for-hire vessels may continue to keep two bass per day, when every other angler on the entire East Coast is subject to a one-fish bag limit; Maryland regulations also include a so-called “trophy” season that targets the largest, most fecund females, fish that are off-limits to anglers everywhere else.

Once again, harvest was given priority, even over a recreational catch-and-release fishery that anglers had enjoyed for years.

A long time ago, freshwater fisheries managers began distinguishing between “panfish” such as perch, sunfish, and bullheads, which are abundant, fecund, and caught primarily for personal consumption, and “gamefish” such as trout, muskellunge, and the various black bass which, while they can be eaten, are pursued primarily for sport. Regulations have long reflected that distinction, managing panfish for yield, and gamefish for abundance and recreational opportunity.

Saltwater fisheries have yet to recognize the difference between panfish and gamefish, and use the same management approach for striped bass, bluefish, and weakfish as they use to manage panfish such as flounder, snapper, and croaker.

It is well past time for that to change.

Pingback: ASMFC Holds Eventful Summer Meeting – Fissues.org

I am a huge advocate of catch and release. I am a professional fishing guide and I try to get all my clients to catch and release. Most will, but some like to take a few home to eat. That is their right, but I try to educated my clients on how catch and release helps our fisheries tremendously.