The Gulf of Mexico Fisheries Management Council this year implemented an exempted fishing permit that allowed the states to set red snapper seasons for federal waters. The program was designed to improve data collection but also increase the number of days on the water for recreational anglers.

When the Gulf Council set a 3-day federal season, the reaction by many anglers was a collective outrage at perceived federal mismanagement. This was before the anglers’ rights groups lobbied certain Congress members to pressure the Secretary of Commerce to extend the season to 42 days, an illegal decision that Commerce declined to defend in federal court.

This year Mississippi closed its snapper season on Friday August 17 (although the state reopened the season September 1 and 2 for the Labor Day weekend). That leaves only Texas, which has the weakest reporting mechanisms and a staunch commitment to allowing snapper fishing in state waters year-round, with any open season. All of the other Gulf states closed their seasons earlier than they had planned and will be closed for Labor Day weekend.

Now that we are seeing the early results of this management experiment, it appears at first glance that the problem with shorter snapper seasons was not that the federal government was persecuting recreational anglers just for the fun of it. The states, freshly armed with better data monitoring through cell phone apps and mandatory reporting in states like Alabama, actually decreased the lengths of their state snapper seasons and the overall number of available days for anglers to be on the water.

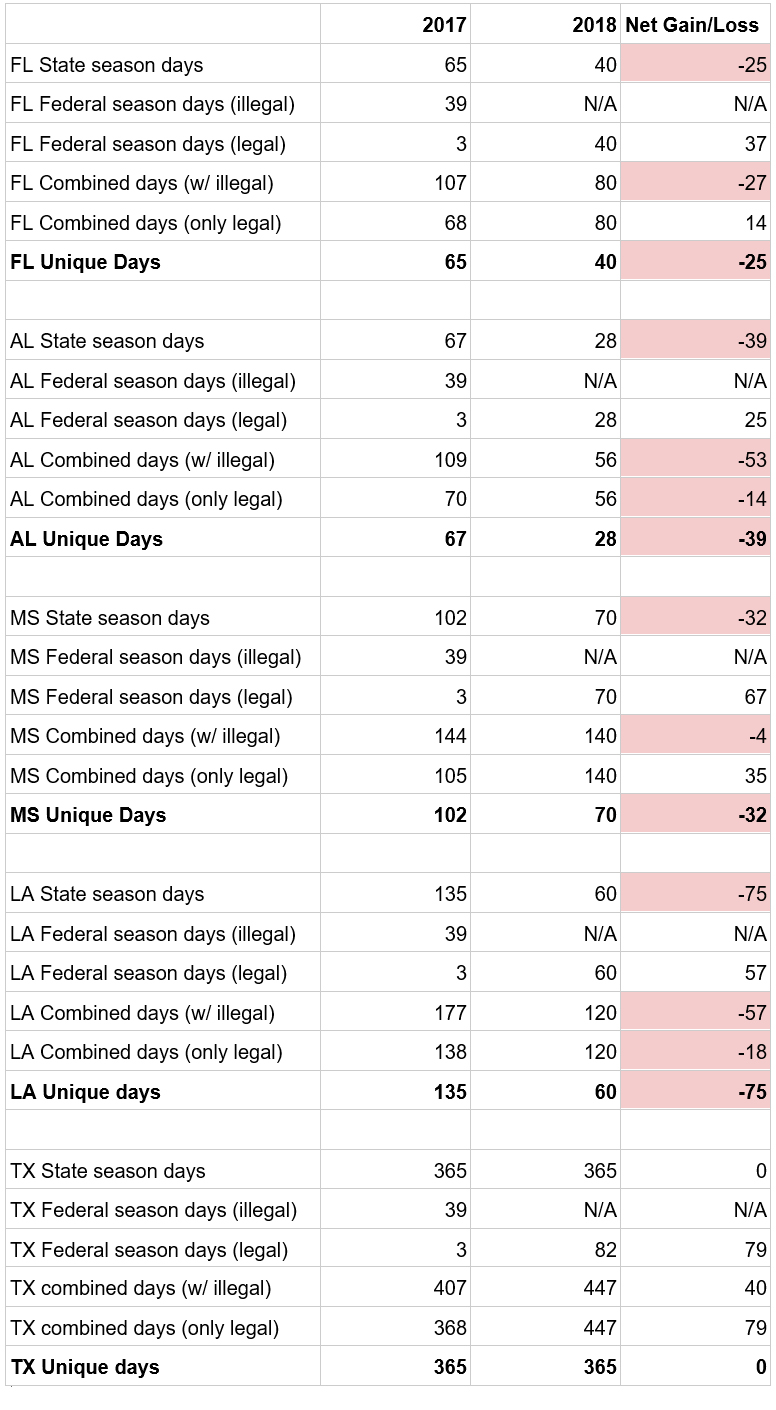

The following data was aggregated by calling or emailing the various state agencies offices and by combing through past press releases. The red shading indicates a decrease in number of days on the water:

Now some of the same anglers who blamed shorter snapper seasons on federal management have been forced to publicly acknowledge what most people who follow snapper seasons have known all along: More anglers and bigger fish means that seasons will necessarily be shorter as long as we continue to manage them by bag limits and numbers of days.

For anglers’ right groups, that means the only other options to catch more fish per person are to attack the science itself and/or to advocate for more fish to be allocated to the private recreational sector. There are already myriad examples of trade groups calling into question the science itself, but “bad science” is explicitly the rationale behind the costly two-year independent snapper count.

Section 204 of H.R. 200, the Magnuson-Stevens Act reauthorization bill that narrowly passed last month and was advanced by the anglers’ rights groups, also attacks fisheries science by allowing economics to be considered when setting annual catch limits, which has previously been a strictly biological question.

Section 202 of H.R. 200 also advances the interests of groups that want more fish through reallocation by mandating 5-year allocation reviews in mixed use fisheries (read: snapper), but only for the Gulf and South Atlantic regions.

When another snapper reallocation dispute inevitable comes up again, both recreational and commercial interests will be poring over historical data.

Recently, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Office of Science and Technology released newly calibrated marine recreational fish catch and effort data for their Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP). To meet the recreational fishing data needs that fit into the overall goal of managing the nation’s fisheries, the program goal is to have a system of surveys operating with consistent standards and sufficient flexibility to meet national, regional, and state needs and provide reliable information about recreational fishing in a timely manner to support effective and fair management.

The new, mail-based Fishing Effort Survey (FES) is a more accurate method of collecting saltwater recreational fishing effort data from shore and private boat anglers on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. In its 2017 review of MRIP, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine called the FES a “major improvement” over the old Coastal Household Telephone Survey (CHTS).

According to research and data queries done by Mississippi Commercial Fisheries United for species such as red snapper, spotted sea trout, redfish, and flounder in the Gulf States, the numbers indicates an increase in recreational harvest over previous estimates by 100 to 300 percent.

For example, recreational spotted sea trout landings in Mississippi more than nearly doubled dating all the way back to the early 1980s. Under the old survey, Mississippi recreational spotted sea trout landings were around 2.1 million pounds in 2016. The new survey indicates that over 5.2 million pounds were actually landed in 2016.

Red snapper is clearly the most coveted species in the Gulf. According to the old survey, the combined estimated snapper landings for all Gulf States were 7,978,022 pounds. The new methodology suggests that 18,509,729 pounds of snapper were harvested by recreational fishers in the Gulf of Mexico.

These newly calibrated statistics are alarming to say the least.

The utilization of these numbers is a foundation of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act that requires fishery management decisions to be based on the best available scientific evidence. The NMFS data is the best scientific data we have for fisheries managers to make management decisions that are fair and equitable for all user groups.

We have seen that recreational sectors across the U.S. have vastly overfished a number of economically important species. Conservationists, environmental groups, fishermen, and seafood consumers should be alarmed that this rate of chronic overfishing is being allowed to take place. All fisheries must be held accountable to ensure the conservation of marine resources for generations to come.

We have all heard arguments from recreational anglers that there are more recreational anglers than ever before and fewer commercial quota holders due to consolidation in the industry. Therefore, because there are more recreational fishermen than commercial fishermen, that means it is more equitable to award more snapper to recreational anglers.

Of course, this ignores the fact that the commercial fishermen are catching fish for people other than themselves. Everyone who eats fish in a restaurant or buys it from a market should be considered a user in the fishery. Those numbers are harder to obtain, but I think few would doubt that seafood consumers vastly outnumber recreational anglers. It’s hard to quantify demand, but there seems to be no shortage of people who want to buy red snapper.

When the Gulf Council met recently in Corpus Christi, snapper reallocation was a big topic of discussion. The fight is likely to be as contentious as ever because, here in the Gulf, everything comes back to snapper.

Kind of funny that when I go to HEB Texas’ almost monopoly grocery, I have never seen a snapper in the display that would not have caused a recreational fisherman to get a fine. Commercial fisherman are trashing our resources by taking huge numbers of young fish.

I think if you can’t catch it yourself you should eat tilapia