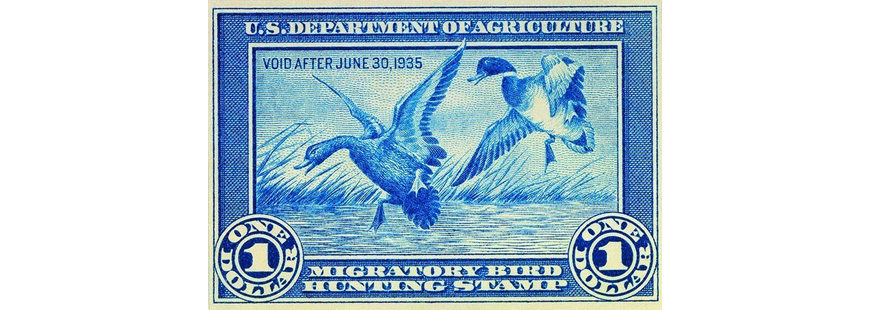

Photo: The first U.S. duck stamp, via Wikipedia

For America’s saltwater anglers, the future will judge us on how we act now

From the early days of European settlement of North America and well into the 19th century, fish and game were plentiful, and there was little need for season restrictions or bag limits. But as the 19th century rolled along and the 20th began, the situation began to change. Having thrown off the hierarchies and social strictures of the old world, American society was organizing itself increasingly around the motive of profit.

In the plains states in the 1870’s, a vogue for buffalo hide coats among Europeans pushed the American bison to the brink of extinction in a few short years. One man, “Buffalo Bill” Cody, killed 4,280 buffalo (he counted) in the course of twelve months. Passenger pigeons were less lucky. Market hunters wiped them out altogether. The last passenger pigeon on earth – “Martha” – died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914.

During the same period, technological innovations were making the harvest of fish and game ever more efficient. The coming of the railroads and the ice industry to towns around the Gulf of Mexico, for example, opened markets for Gulf seafood far from the coast.

But fish and wildlife have not been pressured by market commodification alone. It turns out that the health of game populations is intimately connected to the abundance of another species: man. The human population of the planet doubled between 1804 and 1927. By 1974 it had doubled again. That same period saw the arrival of the automobile, the interstate highway system, radio communication and air travel. A keen angler can now leave his house in Topeka in the morning and be on the water off of Pensacola by mid afternoon.

But if humans are the problem, we are also the solution. Terrestrial species have found strong advocates among sportsmen. George Bird Grinnell spoke up for the buffalo around the turn of the 19th century. J.N. “Ding” Darling, an avid waterfowler, initiated the Federal Duck Stamp program and designed the first stamp. Nash Buckingham saw the writing on the wall for dove hunters and worked at the state and federal levels to put an end to baiting and introduce sensible regulations to save birds for next year’s breeding stocks. And what sportsman doesn’t know the names of Teddy Roosevelt or Aldo Leopold?

Sport hunters introduced and supported successful legislation like the Lacey Act of 1900, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, and the Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937, on account of which much habitat has been conserved. Game birds and many terrestrial species have rebounded to an extent that today we are able to enjoy America’s hunting traditions and pass them on to the next generation. We live off of the foresight and prudence of those sportsmen-conservationists of previous generations, just as future generations will live off of ours. Or not.

Marine fish have been comparatively neglected, in part because for a long time the problem wasn’t so urgent, as overfishing tended to be isolated. Living under water, marine fish are by nature both harder to see and study, and harder to harvest than are terrestrial animals. But the same forces that threatened terrestrial animals a hundred years ago are now looming over our marine fisheries: profit, technology, and (human) population growth. As time goes on, it will become even more crucial that we adhere to science and conservation-based principles in our fisheries management.

Just as previous generations of sport hunters stepped up and spoke out on behalf of terrestrial animals, so now is the time for recreational anglers to step up and speak out for our marine fisheries. We recreational anglers stand at the intersections of politics, science, and management. We will be able to hand on America’s fishing heritage to the next generation only if we work now to protect the resources upon which that heritage is built.

There are more recreational fishermen now than there have ever been. That means more lines in the water, and more competition for fewer fish. But it also means that there is an army of potential fisherman-conservationists that politicians won’t be able to ignore. Now is the time to speak up for smart management grounded in robust data and the best available science. Now is the time to speak up for future generations of recreational anglers. Now is the time to put fish first.