Avoiding Past Mistakes and Keeping The Debate over MSA Reauthorization Focused on the Future

On December 7, 2015 the US House of Representatives’ Committee on Natural Resources held what is called an “oversight hearing” titled, “Restoring Atlantic Fisheries and Protecting the Regional Seafood Economy.” Instead of being held in Washington DC, this was a “field” hearing staged in the town of Riverhead on the East End of Long Island, NY. Field hearings often address controversial subjects of particular concern to that congressional district, and this hearing was designed to do exactly that…sort of.

I earn part of my living as one of the rare stakeholder advocates who work within the fisheries management system. I first learned of this hearing because committee staff was reaching out within the community seeking potential witnesses. A sad reality is that the pool of stakeholder representatives that cover East Coast fishery management bodies is very small. When it comes to the recreational fishing community, whom I have served for almost 20 years, I am frequently the only recreational stakeholder representative at most meetings. It’s not a surprise that my name came up and roughly a week before the hearing date I was contacted by staff, had a brief conversation and received an invitation to testify. Being a first generation American (my mother immigrated from Ireland as a teenager), I was raised to appreciate the ability to participate in government. I take opportunities like this seriously and considered the invitation an honor.

The biggest fisheries issue in Congress these days is reauthorization of our nation’s primary fishing law, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA). The debate over reauthorization has been ongoing since early 2013. I testified before the Senate on this issue in July of 2013. As of today, the Senate has still not had a bill develop enough support for a vote. Some who know more about these things than I are predicting that with the presidential election looming, it is possible this very controversial issue will be placed on the backburner until voters choose the direction of government.

A few months ago, the House however did pass H.R. 1335 titled “Strengthening Fishing Communities and Increasing Flexibility in Fisheries Management Act,” which is why my initial reaction to the hearing was one of confusion. Yes, there were some local issues addressed in the hearing announcement, but most had to do with subjects that are directly related to MSA reauthorization, such as management of summer flounder. I concluded that although the House passed H.R. 1335, the fact that this hearing was held at all hopefully indicates the House is aware much more work and debate needs to occur before comprehensive legislation to reauthorize MSA is complete. This is why I agreed to put almost a week of my life on hold in order to testify. My decision was similar to the old adage that you give up the right to complain if you don’t vote. Yes, the House already passed a bill, but they are asking my opinion on some issues, so off to NY I went.

I am not alone when I say that I am afraid of H.R. 1335, especially the language that would add even more flexibility to MSA. I began my testimony with a message similar to what I told the Senate in 2013, except this time I had real world evidence that many who support the concept of added flexibility would prefer to ignore.

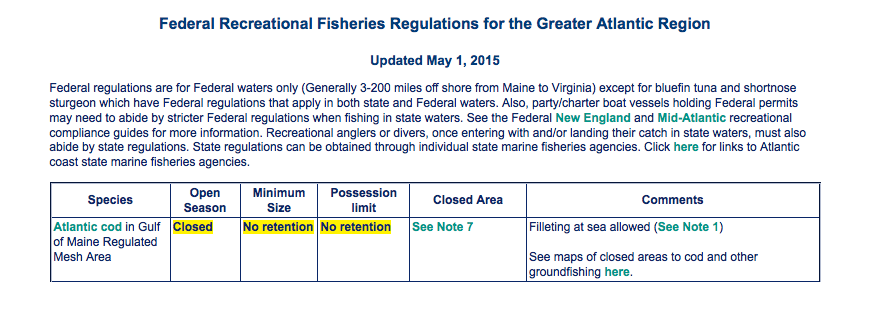

The concept of flexibility in rebuilding sure sounds like forward thinking; however, reality is that management actions tied to this concept are nothing more than a return to the days prior to the last MSA reauthorization. In those dark days of fisheries management, tough decisions were put off for any reason until it was too late for stocks to rebound without significant costs to both fishermen and taxpayers. I believe that Gulf of Maine (GOM) cod management provides an example of the flexibility in management those supporters of H.R. 1335 want expanded. The results of managing GOM cod with existing flexibility are much different than these supporters claim.

This is my view of how flexibility was used in the management of GOM cod. After many years of choosing quotas attached to the highest risk allowed by law, then two more years of false hope that managers used to take even more risk, science caught up with what some fishermen had been saying for years: GOM cod were in significant decline. Using the concepts behind the attractive buzzword that is flexibility, managers delayed significant reductions in mortality while they made a second review of the poor results coming out of the stock assessment. When that did not provide relief, political pressure resulted in even more flexibility under the law, and mortality reductions were lessened while a completely new stock assessment was conducted. The new assessment had no new data besides one additional year of the norm. This is flexibility in action and is already legal under MSA.

Its important to recognize that what I consider the collapse of GOM cod is extremely complicated and should not simply be blamed on fishermen. Environmental conditions changing at a never before seen rate, combined with the high risk associated with flexibility, has made the situation worse. Some supporters of flexibility suggest that since the decline is not the fault of fishermen that fishermen should not have to reduce catch. These voices sometimes acknowledge there are less fish (especially when quotas are not fully harvested) but demand we keep fishing at current levels because we are not at fault. This doesn’t sound like a good long-term business plan and it isn’t. When the excuses for increased flexibility ran out, the mortality reductions were more severe because stock conditions got worse. The government spent money on the repeat of the stock assessment instead of putting needed resources toward understanding how to incorporate the reality of climate change into management. Instead of having Congress allocate money to pay for monitors needed to understand discards, manage small quotas and incorporate complicated management strategies, the Administration was put in the position of declaring another GOM cod related fisheries disaster. Congress allocated additional funds, and those screaming for flexibility were also fighting for another round of taxpayer funded corporate welfare. Does this sound familiar?

Both in her written and oral testimony, Bonnie Brady of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association made the statement, “Federally, our commercial fish stocks are in very good shape.” She also supported this statement with real data about the significant contribution her members make to the regional economy. I couldn’t agree more. She testified that her currently viable and valuable fisheries are threatened by MSA rebuilding and strongly supported the increased flexibility contained in H.R. 1335. She went on to compare flexibility to the length of mortgage loans. Besides the obvious refusal to acknowledge that management under existing MSA language is what produced her members viable and valuable fisheries, I found the comparison to mortgage lending to be the best analogy to explain and discourage flexibility I had ever heard.

Under questioning, I expanded upon the comparison of fisheries management to mortgage rates, suggesting that Congress increasing flexibility within MSA is very similar to allowing banks to increase the subprime lending strategies that triggered the recent national financial crisis. The comparisons are eerily similar and in both cases end up with taxpayers footing the bill for risk-heavy management. Hundreds of thousands of homes were lost due to mortgages given to honest families whose mortgage payments stretched their income to the very edge of their means. These loans left no room for variability in the families income, in the same way flexibility was used to delay mandatory rebuilding of GOM cod and allow continued overfishing. This type of management, whether with mortgage payment or fish stocks, carries with it so much risk that just one unfortunate or unseen situation is likely to put the family or fishing business in a financial hole from which they could not recover. For example, instead of being secure in a house that cost 100 grand (current MSA), banks were allowed to place families into mortgages of double that amount (H.R. 1335). One sickness or bad stock assessment later and the family falls behind on the mortgage, eventually loosing the home. Congress then had to allocate funds to bail out the banks, just like they had to bail out the Northeast ground fish fleet. H.R. 1335 and its concept of flexibility would expand subprime lending of fish stocks. Our nation has already learned this lesson, and Congress should protect our nation and not let it happen again.

MSA in its current form is delivering sustainable fisheries far more often than in the past. Yes, there are issues, especially along the east coast; however, increasing flexibility and continued overfishing will not solve those issues. Congress should be strengthening MSA and pouring every available resource into developing and encouraging forward thinking management. Understanding climate change, accelerating the transition from single species management to multispecies ecosystem models, protecting the forage needed to sustain robust fisheries and better understanding recreational fisheries catch and financial impact are the subjects Congress should be discussing as we move closer to a reauthorized MSA. The one thing I trust is that our system of democracy works and that in the end, after all the debate and rhetoric is over, we will have a reauthorized MSA that finds the balance between conserving our natural resources and managing sustainable commercial and recreational fisheries that contribute to our nation’s economy. Until that time, let’s keep the conversation moving in a positive direction by building upon the current success of MSA, adjusting for our changing climate and preparing for the future.

Pingback: Magnuson-Stevens Reauthorization: There’s No Escaping Reality | Marine Fish Conservation Network