Commercial and recreational fishing; photo by John McMurray

H.R. 200, the “Strengthening Fishing Communities and Increasing Flexibility in Fisheries Management Act,” is scheduled to come to the House floor for a vote on Wednesday, July 11th. The Network and its partners oppose this bill because it undermines the strong science and conservation measures within the current Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act and promotes greater uncertainty in the future management of our fisheries.

The House vote on H.R. 200 comes on the heels of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) annual Status of U.S. Fisheries report to Congress, which is based on stock assessments that the agency conducted during that year. This latest report is more proof that the science-based management mandated by Magnuson-Stevens continues to improve the health of our fisheries.

According to NOAA Fisheries Administrator Chris Oliver, “Status of the Stocks provides a ‘snapshot in time’ of the status of our nation’s fisheries last year.” Oliver’s choice of the word “snapshot” is an important distinction. NOAA Fisheries, also commonly known as the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), tracks 474 fish stocks or stock complexes (multiple stocks with common traits grouped together as one stock). Conducting stock assessments—defined by NMFS as a scientific analysis of the abundance and composition of a fish stock, as well as the degree of fishing intensity—on all of these stocks takes tremendous time and effort. The reality is that NMFS has neither the time nor resources to conduct annual stock assessments on every stock it manages. For example, NMFS conducted 216 stock assessments in 2017, which was “the most ever completed in one fiscal year.”

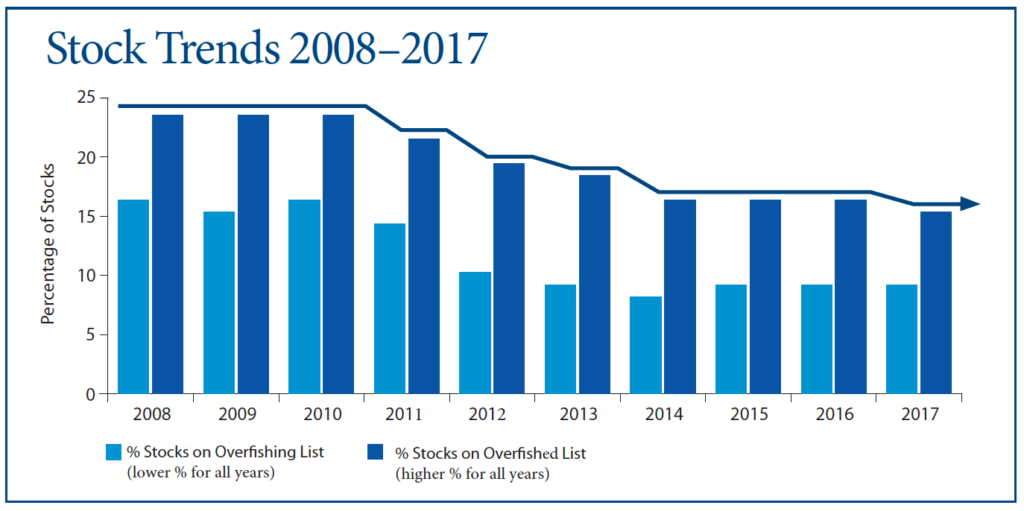

Although this snapshot provides valuable insight into how our fisheries are currently doing, what’s crucial to pay attention to is the trend over time that the annual Status of Stocks report provides. As this chart in the report shows, the numbers of stocks on the overfishing and overfished lists have been declining since 2008:

This downward trend is not surprising to those who understand the progress made during the last reauthorization of the Magnuson-Stevens Act, which significantly strengthened the use of science and accountability in fisheries management. In the 2006 reauthorization, Congress mandated that all regional fishery management councils set science-based annual catch limits as part of their fishery management plans and accountability measures for overages in catch quotas. Overfishing could no longer legally go unchecked, and overfished stocks were required to have rebuilding plans that had a fair chance of succeeding within a ten-year timeframe for most stocks. NMFS’ annual snapshots of our fisheries show the impacts on overfishing and overfished stocks that these management improvements made from 2006 when the law went into effect (and was fully implemented over time) to the most recent stock assessments available today.

The big picture derived from NMFS’s Status of Stocks report to Congress is that the Magnuson-Stevens Act is working. Not only are the numbers of overfished and overfishing stocks declining, but also 44 stocks have been rebuilt since 2000.

Overall, that’s a pretty picture.

This picture, however, could get uglier with the next reauthorization. There’s been a shift in dialogue around Magnuson-Stevens in the last few years, which was echoed in Oliver’s leadership message about the Status of Stocks report:

“With this sound science as our backbone, I believe that there is still room for flexibility and a greater role for common sense in our approach to fisheries management. I am bringing a more business-minded attitude to that process.”

Those who have been following the debate over the current Magnuson-Stevens reauthorization know that “flexibility” is often a buzzword for relaxing science-based catch limits on some fisheries or with some sectors. In other words, “flexibility” is about undoing the progress we’ve made since the 2006 reauthorization of the Magnuson-Stevens Act.

It’s no coincidence that “flexibility” appears in the bill title of H.R. 200.

For industries, businesses and individuals that rely on these finite public resources, eliminating science-based catch limits that ensure the long-term sustainability of fish populations is anything but “common-sense” or “business-minded.” It’s common sense that fishing-related businesses—both recreational and commercial—have greater success when there’s more fish to catch.

Passing H.R. 200 and weakening science-based annual catch limits would undermine the progress our nation’s fisheries have made in the last 10 years under the current Magnuson-Stevens Act. Our own history has shown that fish populations are healthier under science-based catch limits and accountability measures.

Today, we have healthier oceans and more productive fisheries, which has led to greater financial and economic security for coastal businesses and communities up and down our coasts. That’s a report we should all share with Congress.

Tell Congress now to vote no on H.R. 200.