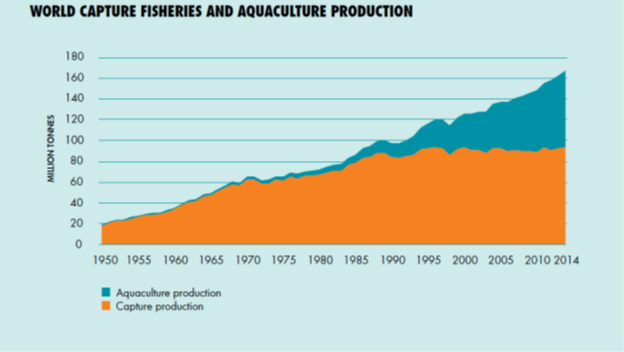

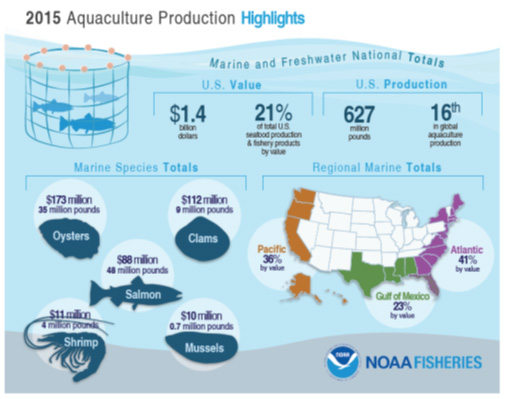

According to short term projections by the Food and Agricultural Organization (or FAO), global fish demand could increase by 47 million tons in less than ten years. In the last several decades, despite rising seafood consumption, wild-capture fisheries’ production remained steady, while aquaculture production grew to help meet this demand. The United States is not currently a major producer of farmed seafood on a global scale, but there are operations on every coast. The Pacific coast produces a large amount of salmon in offshore cages. Off-bottom cage culture for oysters is common on the east coast.

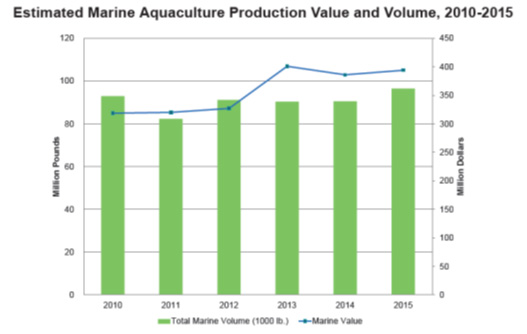

Aquaculture production in the U.S. is trending slightly upward, and the value of species produced increased in the last few years, making a 22% jump in value between 2013 and 2014. The messaging around aquaculture is conflicting: is it the solution to an impending global food crisis and shortage of wild-capture seafood, or is it an environmentally damaging alternative to wild, sustainable fish and shellfish? Despite these conflicting narratives, aquaculture is quickly becoming a priority in the domestic seafood industry, and commercial fishermen are making sure they’re involved in these conversations.

In general, the Gulf of Mexico region lags behind the rest of the country in aquaculture trends. Texas, Alabama, and Florida have inland farms for Pacific white shrimp. One can make the argument that oysters have been “farmed” in some Gulf states on private leased grounds, but off-bottom cage culture is a relatively new industry. The successful banning of commercial harvest of redfish in the 1980s by Coastal Conservation Association necessitated the development of inland farms in Texas as a consistent, domestic source of redfish. According to Congressional testimony from Chef Haley Bitterman, Executive Chef and Director of Operations for the Ralph Brennan Restaurant Group, “the only fish we serve at Redfish Grill in New Orleans is farmed” due to the fact that “commercial fishers remain completely shut out” of the fishery.

Recently, NOAA, Congress, and the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council have focused on the possibility of growing offshore aquaculture in the second most productive area of wild seafood in the U.S. NOAA’s Final Rule to implement aquaculture in the Gulf of Mexico was published in 2016. At its April 2018 meeting, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council approved an Exempted Fishing Permit for an Almaco jack fish farm off the coast of Florida. Representatives from the Gulf Coast seafood industry, along with state elected officials, have toured northern operations in an effort to use these businesses as models for this new industry.

The commercial fishing industries of the Gulf, and around the country, are carefully watching these operations develop. There is a wealth of literature highlighting concerns around aquaculture. Negative impacts include, but are not limited to, water pollution from fish waste, excess feed, and medications; sedimentation of bottom habitats from solid waste from open ocean pens; the protein cost-production ratio as forage fish will be needed for feed and removal of too many of these fish could affect the natural food-chain; and genetic and disease transfer between farmed populations and wild stocks. The public eye turned to the risk of mass escape events due to recent failures in the Pacific Northwest. Because of these issues, without careful planning, aquaculture in the Gulf has the potential to create more harm than good.

Commercial fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico work hard to conserve wild fish and shellfish populations and are not opposed to new opportunities for seafood production. Rigorous management and regulatory process needs to ensure that these operations develop with careful planning and formal opportunities for input from the commercial fishing industry, creating a scenario with maximum economic benefit and with minimal environmental or economic harm.

It is imperative that aquaculture developers engage wild commercial fishermen to ensure that these industries co-exist and fill independent markets, instead of aquaculture emerging as an obstacle to successful commercial businesses. While aquaculture opportunities could be promising, it is vital that proper protections for wild populations and the commercial wild-capture industry are put in place, and that businesses seeking to develop these operations proceed with caution.