I remain a bit perplexed as to why our Pacific Coast groundfish remain so less controversial than those on the east coast. Having just come from another trip to Washington, DC, where both sport and commercial fishers were “working the hill” on Magnuson-Stevens reauthorization, it was good to see the common goal of preserving such a mutually beneficial piece of legislation.

I was still pretty young (and naïve) when the big west coast groundfish fleet buy-out was happening due to the drastic cutbacks of harvest for many species of commercially valuable groundfish. That was happening in the early 1990’s. I didn’t have the context or perspective I have now, but it was easy to realize that it dealt a devastating blow to a once big-time economic component of the rural coast of Oregon. The downfall (and subsequent evolution) of the oldest town west of the Mississippi (Astoria) was complete. The fur trade was first to arrive, until humans decimated all the otter and beaver. Then salmon dominated the landscape, but then between the over-harvest by the gillnet fleet and the onslaught of the hydropower system, salmon fisheries collapsed. Bumblebee packing was once headquartered in Astoria, but moved on by 1980. By then, timber was king, until guess what, between the Tillamook Burn and over-harvest of timber, that industry became a fraction of its historic self. Then it was on to groundfish, where early abundant catches were perceived as inexhaustible.(I know, where have we heard that before?) .

Are you seeing a pattern here? Human “management” is like the opposite of King Midas, everything we historically have touched, turned to ash, or in real life, scrap metal. Oh yeah, recently the sardine fleet only lasted less than a decade in Astoria.

Of course now we have better science and better understanding, and our managers and fleets have taken on greater responsibility to ensure that future generations of fishers actually get to fish. It’s likely that none of this would have happened if our communities never saw their rock bottom. Rock bottom often causes a prolific change in one’s mentality, attitude or behavior; oftentimes its a necessary evil.

The question remains for me, however, which is how are we on the West Coast finding it a little easier to embrace conservation measures over the East Coast? Are their coastal communities not such a destination draw for tourism like those in Oregon? Are their commercial fishing fleets so much more established than those of the west coast, so entrenched or invested in their fisheries? Are west coast waters so much more under-capitalized with a sportfleet that targets groundfish that there’s less contention? I don’t know east coast fisheries enough to answer that question, but from what I’ve heard, there’s little hope for an easy solution.

It makes the case for foreshadowing the future, and addressing serious problems before they become real problems. Of course hindsight is 20/20, but if we look at worldwide trends, the future is already before us. There is a reason the foreign fleet was fishing what are now U.S. waters before and after Magnuson-Stevens came into existence; they had already fished down all of their own stocks of fish and needed to find greener pastures farther and farther away from their home waters.

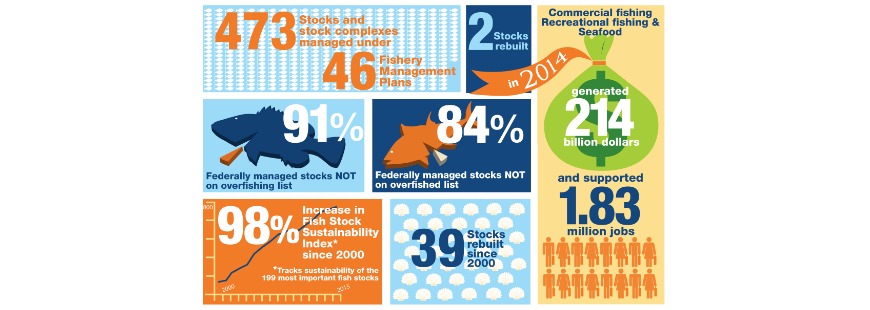

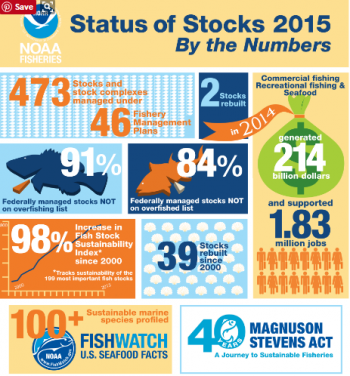

Although there’s always reasons to look at long-standing laws to see if there’s room for improvement, but those charged with looking at provisions to improve are not finding a need for drastic changes in the law. It’s a sign that the law is working, as it was intended to do. What communities of fishermen and conservationists should be aware of are intentional rollbacks of provisions that have proven themselves effective in delivering as promised. A consistent result of rebuilding once-depleted stocks of fish is an example that stands alone.

A strong Magnuson-Stevens will still require broad-based support from across the various sectors. If history repeats itself, and it will have to in order to keep the law in working order, conversations between fishers (both sport and commercial), along with the conservation community, will have to happen. The good news is, those conversations have gone well in recent history, as trust again begins to build due to the successes we’ve historically seen. All sectors of our nation’s citizens want to see robust stocks of fish that continue to feed our citizens and even get shipped overseas where markets remain strong. Robust fisheries are good for everyone, and we want to keep it that way.

It was great seeing a strong turn out of all fishermen in Washington, DC this week. It shows that those most invested in the resource are those most invested in the future success of these fisheries. Of all the conversations that I’ve had with fishermen from both the sport and commercial fleets, no one wants to harvest the last fish from our oceans and rivers. We all want to see the same or better opportunities for our children, as we’ve enjoyed in our lifetimes. The only way to do that is to look ahead at the future threats our fisheries face and head them off at the pass, but more importantly, look at our past practices, and what got us there in the first place.

My issues as well as millions of others is recreational fishing for Red Snapper is not fair or equitable with charter or commercial. I have been an outdoorsman my whole life and I believe in conservation but what we are experiencing rules set by Federal agencies that are not based on good science. 3 days of Federal fishing for recreational purposes is a slap in the face. The chances of weather and seas is always a factor. There is a good chance we will not even be able to go out those days. The charter guys have 49 days and will make the most of it with multiple trips per day. It is the opinion that this is Federal overreach and I would hope that the powers that be do a better job of surveying the population or get out of the oversight all together.