This article originally appeared in the Wild Oceans Horizon newsletter.

Meeting the Challenge of a Shifting Prey Base

The Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council’s Unmanaged Forage Omnibus Amendment (UFOA) stands as a testament to the value of stakeholder engagement in our fishery management process. The amendment “prohibits the development of new and expansion of existing directed commercial fisheries on unmanaged forage species in mid-Atlantic federal waters until the Council has had an adequate opportunity to assess the scientific information relating to any new or expanded directed fisheries and consider potential impacts to existing fisheries, fishing communities, and the marine ecosystem.” Sixteen taxa of forage species are conserved through a 1,700 pound combined possession limit.

Within the UFOA, the public is credited for bringing the issue of forage fish conservation to the Council’s attention during a 2011 visioning initiative that involved extensive stakeholder outreach and identified management of forage fisheries as a key concern. Public support during the UFOA’s development from 2015-2017 was no less remarkable. Over 21,000 petition signatures and 150 written letters from individuals and organizations, representing anglers, watershed stewards, scientists and environmentalists, were received along with over 600 poems, drawings and pledges from young ocean advocates.

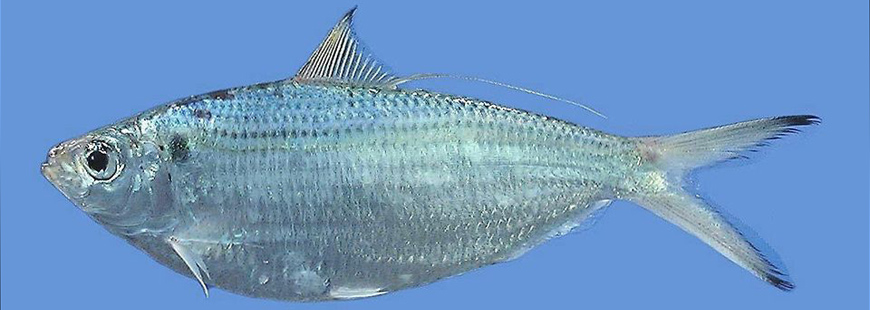

Now the will of the Council and its constituents is being tested. NOAA’s Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office (GARFO) is considering whether to green light an exempted fishing permit (EFP) to explore the development of a new high-volume fishery for Atlantic thread herring (Opisthonema oglinum), one of the species currently safeguarded by the UFOA possession limit.

Atlantic thread herring were included in the amendment because they, along with other herrings, are eaten by council-managed monkfish, bluefish, summer flounder, black sea bass and spiny dogfish as well as by protected whales, dolphins, porpoises, seals and seabirds. Despite their ecological importance, very little is known about Atlantic thread herring in U.S. waters, and the status of the stock is uncertain.

When creating the UFOA, the Mid-Atlantic Council made it clear that fishery prohibitions for unmanaged forage fish were not indefinite. EFPs were chosen as the method by which the Council would consider allowing new fisheries or the expansion of existing fisheries. However, no specific criteria were outlined to evaluate EFP applications for consistency with the UFOA objective and with the Council’s long-standing ecosystem policy, “to support the maintenance of an adequate forage base in the Mid-Atlantic to ensure ecosystem productivity, structure and function and to support sustainable fishing communities.”

The EFP application filed by Lund’s Fisheries out of Cape May, New Jersey calls for trip limits up to 100,000 pounds (nearly a 60-fold increase from the current possession limit) using purse seines that are 2,000 feet long and 180 feet high (roughly twice the size of a purse seine deployed by the Atlantic menhaden fishery) in federal waters from New York to Virginia. No at-sea monitoring of bycatch is proposed.

Alarmed by the scope of the requested Atlantic thread herring EFP, the potential for bycatch of feeding predators and other small pelagic fish (depleted river herring and shad among them), and the damaging precedent approval of the EFP would set, Wild Oceans was joined by the American Sportfishing Association, Coastal Conservation Association, Conservation Law Foundation, Great Egg Harbor Watershed Association, Gotham Whale, International Game Fish Association, Menhaden Defenders, National Audubon Society, Rhode Island Saltwater Anglers Association, Riverkeeper, Inc., Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and the Virginia Saltwater Sportfishing Association in submitting a letter to the Mid-Atlantic Council’s Ecosystem and Ocean Planning (EOP) Committee ahead of an October 4 meeting to review the EFP application.

In the letter, we opposed advancing the EFP application for further consideration and recommended the Committee turn its attention to developing standards for endorsing EFP applications for new or expanding forage fisheries. While committee members expressed mixed views about the merit of the Lund’s Fisheries EFP, they did agree on the need to develop an EFP review policy/process, and that initiative is being considered as a potential 2022 priority. Ultimately, authority to approve or deny an EFP application resides with GARFO’s Regional Administrator, who must determine that the purpose, design, and administration of the EFP are consistent with management objectives and the Magnuson-Stevens Act. A clear EFP policy would help ensure rigor and transparency when EFP applications are reviewed.

When creating the UFOA, the Mid-Atlantic Council, along with the thousands of stakeholders who weighed in, recognized that a pathway to ecologically sustainable new fisheries must include strategies to improve our understanding of ecosystem impacts. This includes recognizing that climate change affects prey populations and their availability to predators.

Just 10 years ago, the Atlantic herring and Atlantic mackerel quotas were 91,200 mt and 46,779 mt, respectively. This year, the Atlantic herring quota was just 4,651 mt, and the mackerel fishery closed after landing 5,200 mt to avoid continued overfishing. Because of unexpectedly low productivity, rebuilding these overfished stocks will take time. It’s possible that quotas will never reach the peak years of the past.

As fishermen seek opportunities to shift to new target species, like Atlantic thread herring, our fishery management programs must take into account that the changing composition of the forage base is affecting predators as well as existing forage fisheries. This is the forward thinking, ecosystem approach to fisheries management that laid the foundation for the Unmanaged Forage Omnibus Amendment, an approach that should be upheld by NOAA Fisheries.

Atlantic thread herring photo via NOAA/Wikimedia